An Academy Divided: A Decade of Exclusion

February 20, 2020

Part of the joy of going to the cinema is seeing an aspect of yourself up on the screen. From a young age, we connect as a movie-going audience with the characters who emulate us, the films that represent us, and the actors who look like us. We imagine ourselves in the worlds of the stories, and they fill us with a multitude of emotions. Yet, there is a disturbance in the Force, for some of the people that we see on the screen do not get the attention and respect of the industry, and there seems to be a common thread joining them.

On January 13, 2020, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences announced their nominations for the 92nd Academy Awards, which had its telecast on February 9. Almost immediately following the announcement (and in fact during the announcement by one of the actors who announced the nominees, Issa Rae) the entire industry, awards pundits, and the movie going public expressed their disdain for the lack of representation in the nominees. Many have said that the Academy is not recognizing the great work of non-white and non-male talent. So, I wanted to take a step back and look at this issue in full. Is the Academy racist? Is the Academy sexist? One year cannot decide this alone, so I decided to look at the decade that just came to a close. Not only will this provide a good 10 years to work with to try and find the answers, but it should be noted why this decade is so important in the history of the Oscars.

In 2010, history was made when Barbra Streissand said the following words, “Well the time has come. Kathryn Bigelow!” For the first time in Academy Awards’ history, a woman came to the stage to accept the Best Director Oscar. Bigelow won for her gripping war drama The Hurt Locker, which went on to win a total of six Academy Awards, including Best Picture. 2010 was a landmark year for honoring diverse talent in film, and now the test was set. Would the Academy continue to honor diverse talent after Bigelow, and would they expand to honor even more? This is why looking at the past ten years since The Hurt Locker will provide the answers.

Now, one of the major topics of conversation is whether the Academy has a male-centric lens. A number reported in 2016 was that the Academy was 91% white and 76% male. These numbers are staggering for a branch of filmmakers that are supposed to be representative of the entire industry. Now, the best way to view whether the Academy has a problem with diverse talent, let’s look at the films that have been selected for Best Picture in the past decade.

If one looks back on the Best Picture category, they will see that there have been 88 nominated films in the category from 2011-2020. Let’s look at the Academy’s relationship with female talent first. After some quick arithmetic, these were the numbers I discovered. Out of the 88 nominated films, 28% of them had a female lead or female co-lead, the other 72% being films with male leads. 7% were films directed by a woman, and 6% were films directed by and starring a woman. These statistics benefit the narrative that the Academy does seem to favor male centric films, and if you’re thinking that maybe they are getting better, they really are not. This year saw two of the nine nominees for Best Picture have female leads or co-leads: Noah Baumbach’s Marriage Story and Greta Gerwig’s Little Women. Speaking of Greta Gerwig, possibly the greatest topic of contention following the nominations were no female directors nominated in the Best Director category. But the trend that was set with Gerwig was even more unsettling than the Academy just ignoring female filmmakers. Gerwig is the fifth woman in history to be nominated for Best Director, for her 2017 film Lady Bird. With her sophomore effort, she missed the nomination, the same as Kathryn Bigelow, whose follow up to The Hurt Locker, 2013’s Zero Dark Thirty, got a Best Picture nomination but missed a Best Director nomination for herself. The Academy seems to not want to honor female filmmakers, not even those that have been previously nominated before.

Overall, female led and directed films do not have a great showing at the Academy Awards, especially in the last ten years when the talent has been increasing. 2011 saw the only year where two of the nominated films for Best Picture were directed by women, and 2018 saw the highest amount of female led films in Best Picture, but it should be noted that 2018 was the year of the #MeToo Movement, which probably contributed to the surge of female led films. Also, only one male led film directed by a female director has had their film nominated in the Best Picture category, that being 2014’s Selma by director Ava DuVernary. She did not get a nomination herself in the Best Director category, which would’ve made her the first African American female director to be nominated.. And this issue is not tied to the top categories alone. Throughout all the categories, female led and centric films are ignored for recognition. Frozen II, the highest grossing animated film of all time, did not get nominated for Best Animated Feature. Many expected it to be nominated, not only because of its popularity, but the critical reception was positive, with the film being certified fresh on Rotten Tomatoes. But it missed the cut, and it should be noted that it was the only contender in the category with a female lead, where the five nominees in the category all have male leads. As anyone can see, female directors do not get the recognition they deserve. In fact, female led films by male directors have a better track record than female led films by female directors. And the Academy does not reflect an overall problem with the industry itself. In the past ten years, 40% of the highest grossing film of each individual year had a female lead, so women are seen when it comes to box office, but not awards.

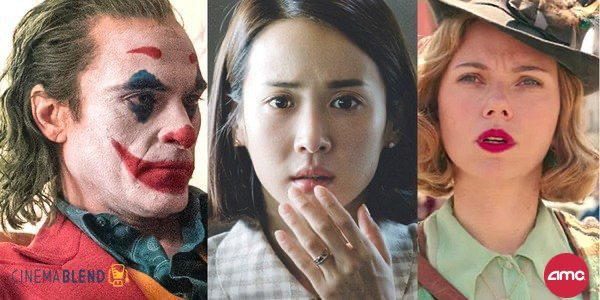

Now, another glaring problem with the nominations released this year is the lack of racial diversity, especially among the acting branch. Nobody is talking about the fact that African American directors are overlooked every year, with only five African American directors being nominated in the Best Director category ever. So to put it clearly, out of almost 425+ directors who have been nominated in Best Director throughout the years, only 10 of them have gone to non white filmmakers. 19 out of the 20 acting nominations are for white actors, with the one diverse nominee is for Cynthia Erivo in Harriet. So, the Academy basically repeated and #OscarsSoWhite, save for nominating one black actor for playing a slave, despite a plethora of talented and groundbreaking performances from diverse talent, be it Lupita Nyong’o in Us, Awkwafina in The Farewell, Jennifer Lopez in Hustlers, Kelvin Harrison Jr. in Luce, Eddie Murphy in Dolemite Is My Name, and more. The Academy is still their traditional selves despite expanding their members to include more diverse talent. With these nominations this year, the complete shut out of non-white actors in 2015 and 2016, and the Academy routinely honoring films like Green Book, which won Best Picture in 2019, and other films that are culturally insensitive to modern audiences. In the past ten years, only nine African American actors have gotten an Oscar nomination in the lead acting categories, be it Best Actor or Best Actress. Out of the nine, two of the roles were for playing slaves, two of the roles were tied to the Civil Rights Movement, and three of them were for Denzel Washington. So that means only two actors in the past 10 years, out of 100 spots for actors, were nominated for performances not tied to race or being Denzel. This is incredibly disturbing, as the amount of working and fantastic African American actors that are not recognized by the Academy. In the Best Picture category, 15% of the nominees in the past ten years had a non-white lead, and 16% of the films were directed by a non-white filmmaker. And just to note, the year that saw the most films nominated for Best Picture with non-white leads was the year after #OscarsSoWhite, so just like with the #MeToo Movement, the Academy piqued up when they were called on their problems and then went right back to their norm the following year.

The last problem that affected these nominations was the shortened awards season this year. The Academy pushed up the telecast from the fourth weekend in February to the second, which you may not think is a big deal. But the effect this has on the industry and so many films is a huge problem, that of which can be reflected in the nominations. Films released at Christmas with the intention to expand later in January do not have the time to gain the attention that films in past years could. Films like Uncut Gems, Just Mercy, and Clemency have no time to get the attention of voters because the nominations have to be sent in before they hit wide release across the country. A film like Just Mercy would have benefited greatly from this, as it garnered an A+ CinemaScore from audiences, and would have resulted in the word of mouth about the film getting this diverse death row drama. But since the nominations were due before the film hit wide release, that possibility was thrown out the window. In fact, in the Best Picture category, eight out of the nine nominees were released after October 1, and in the top 8 categories which has 44 spots available, only six of them were for films released before October 1, and five of them belonged to the same film. There is no way Academy members can see all the films that should be in the conversation if they are all released within 90 days. This is why the nominations this year saw a lot of the same films nominated in almost every category. There are 104 spots open for narrative features, and 66% of the nominations are from films with repeat nominees.

As anyone can see, the Academy has a problem. They do not have enough time to see the lesser known films from diverse talent, and because of this, routinely honor more white and male led films. If the Academy changed the way they vote, possibly moving to a jury based system, maybe it would improve. If there was not a bias against films that come out before October, that would solve these problems, as films like The Farewell and Hustlers, which were both female led, female directed films would be represented if that were the case. But above everything else, diverse talent needs to be represented. One nominee should not make the Academy breathe a sigh of relief. So what is the solution? This may seem like a joke, but it’s to watch the films. You would think that if you are an Academy member, it’s a given to watch all the films in contention, but in the past ten years, Academy voters have voiced the following opinions. Some called Black Panther “the stuff that oozes out of dumpsters behind fast-food restaurants” and then admitting they haven’t seen it, or saying that Lady Bird and Little Women don’t apply to men without having seen it, or that Get Out is not an “Oscar worthy film” without having seen it. If you are a member of the Academy, you have to start watching these films, as they are a part of the film culture that are breaking boundaries in the industry. And even with the groundbreaking wins for Bong Joon-Ho’s Parasite, being the first non-English language film to win Best Picture, who knows what would’ve happened if the nominations were different, and the Academy was choosing different films. Films from diverse talent and showcasing different cultures like Parasite need to routinely be represented among the nominations. If the Academy does not do this, then they are going to fade away from cultural importance as if Thanos snapped his fingers.

Note: The opinions expressed by the author are solely his own and do not represent the views of the Bulldawg Bulletin or Haddonfield Memorial High School.